Tags

Arthur Phillips, book review, courtier, Elisabeth I, England, heresy, historical fiction, innocence, Ottoman Empire, religious conflict, sixteenth century, violence and culture, Wars of Religion

Review: The King at the Edge of the World, by Arthur Phillips

Random House, 2020. 265 pp. $27

In 1591, Mahmoud Ezzedine lives a fulfilling life. As court physician to the Sultan Murad in Constantinople, Mahmoud is highly respected, and his general practice gives him a deserved reputation as a skilled, empathic healer. He has a comfortable house, a beautiful, loving wife, and a son whom he dotes on. Truly, Allah has blessed him.

But a diplomatic mission to London, of all places, is setting forth, and Mahmoud, who’d rather not go anywhere, is dragged along. He has little choice, really, for Murad the Great’s command is law. However, the official who gives the Caliph of Caliphs the idea to send the doctor with the diplomats lusts after Mahmoud’s wife. As a kind, honest person who prefers directness to invasion or suggestion, Mahmoud’s no match for that particular courtier, or any other, for that matter. And you just know, even if you haven’t read the jacket flap — don’t — that the good doctor will make an innocent mistake, for which he’ll pay dearly.

If you’re like me and get upset when you read about decent people suffering for their virtues while the evil triumph, The King at the Edge of the World will make you ache. For that reason, short as the novel is, and recounting as riveting a story as you could want, the threats to our hero kept me from plowing through. Do read the book, though — but not, repeat, the jacket flap, about as potent a spoiler as you’ll ever find.

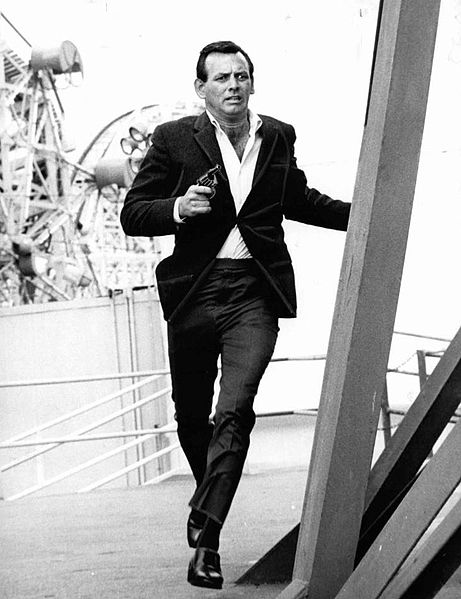

Sultan Murad III (d. 1595) by an unknown Spanish artist (courtesy Wikimedia Commons, public domain). As his first act upon accession to the throne, Murad had his five younger brothers strangled.

Phillips excels at re-creating historical attitudes, prejudices, and ways of reasoning. Mahmoud’s adventures in England also resemble a thriller’s in their ever-increasing intensity; combined, these elements make a strong, thought-provoking narrative. At its center, Phillips puts the England riven by conflict between Protestant and Catholic and imagines how a Muslim would view that. It will be recalled that Elizabethan politics and diplomacy revolved around who prayed where, and in what way, and how many people died, often in hideous fashion, for doing it wrong or attempting to make everyone else do it their way. Hard to imagine that all this idiocy happened during an age blessed with cultural triumph — and Mahmoud, the observant Muslim, remains unimpressed:

He was there, he reminded himself, to be a figure of strength and confidence in the face of endless strangeness, of threats to health and mental stamina. He must fortify the bodies of the embassy’s men (himself included) and fortify their minds against all that was wrong here: the half-naked women, the food, the fog, the filth, the intoxicating drink, the intellectual softness, the islanders’ several varieties of devoted and violent false faith.

The physician, if he weren’t a member of a diplomatic mission, would be called a heretic and a savage to his face (as some English folk manage to imply even as they think they’re being polite). But who’s the person who embodies religious virtue, and who are the real heretics? Who’s the savage, and who’s the civilized, cultured man? This is how Phillips casts the sceptered isle in its glory. To be sure, he also creates an English narrator who insists that Catholic plots against the realm do exist and, if not crushed, would cause widespread bloodshed. Since he’s utterly credible, the question then becomes how to square the civilization and the savagery; and of course, there is no real answer.

My only objections to this novel — have I mentioned the too-revealing jacket flap? — concern Mahmoud’s role as a political actor. How could such a guileless innocent occupy any court position, let alone that of a physician, with the power to kill as well as heal? After all, history records how Ottoman crown princes, on attaining the throne, might have their brothers strangled with a silken cord, as Murad did. Only the politically adept would survive such an atmosphere, or even be invited into it.

Similarly, as the narrative progresses, Mahmoud learns a thing or two about survival — not easily, mind you, and requiring excruciating mental gymnastics, which Phillips ably portrays. For that reason I don’t entirely accept the end, which the author fudges somewhat, unwelcome in itself.

Nevertheless, I invite you to read The King at the Edge of the World and be amazed at Mahmoud’s ingenuity — and his creator’s.

Disclaimer: I obtained my reading copy of this book from the public library.