Tags

1820s, camaraderie, fathers and sons, fur trade, historical fiction, loyalty, nineteenth century, Northwest Territory, Shannon Burke, St. Louis

Review: Into the Savage Country, by Shannon Burke

Pantheon, 2015. 248 pp. $25

“Since I was a boy,” says William Wyeth, the trapper who narrates this novel, “I’d known I was made of different stuff from my brothers. They were born to the plow and pew while I craved the forest and woods and the vast, wild spaces. For better or for worse, I was fated to test my mettle in the west.”

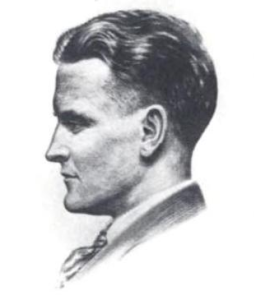

George Caleb Bingham, Fur Traders Descending the Missouri, 1845 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, courtesy Wikimedia Commons. Public domain, US)

It’s the late 1820s, and the fur trade is petering out. To join a trapping brigade in St. Louis and venture northwest into unmapped territory seldom brings a man more than a pittance for his hard labor; it’s more likely he’ll die than make his fortune. But Wyeth goes anyway, and not just because he must prove himself, though he doesn’t understand all the reasons yet.

There’s a woman, of course, a pretty, independent-minded widow named Alene, and Wyeth wants to be somebody so that he may court her. But women are an afterthought in the wild and in this novel; the real story is the bond among men who daily risk their lives for one another. As a neophyte, Wyeth learns that the easiest way to earn trust is to admit that he doesn’t know everything and to laugh at his own mistakes.

Most frontier tales I’ve read seem populated by knuckleheads who equate infallibility with manhood and mistake vulnerability for weakness. Wyeth knows better and grows because of it. Into the Savage Country depicts the knuckleheads to the extent that back in St. Louis, pride runs high, and perceived insults require a forceful response. It’s a settlement, after all, with its pecking orders and privileges. But in the wilderness, there’s less room for preening or posturing, because life’s demanding and dangerous enough without that distraction.

I felt as if the enormity of the land were squeezing me and that I was dissolving into the utter silence and implacability of that immense, monochromatic, edgeless place. This oppressive heaviness and strangeness washed over me bit by bit until I understood what I was feeling: I was afraid. Afraid that I would not measure up to the others, and that I would fail in the tests that inevitably lay ahead. Afraid, too, that I would be slain in some lonely place with no one to mourn me, as my father had predicted.

So it’s very intriguing that the closest bonds Wyeth forms are with two other men whose fathers have declared they’ll never amount to anything. There’s Ferris, who initially strikes Wyeth as a callow showoff but whose perceptive observations about nature, Native American customs, and how to get along with difficult people reveal a depth Wyeth appreciates. That’s one of Wyeth’s best qualities, the willingness to revise an opinion. However, Layton, a dandy who’s done some truly despicable things, seems intent on testing Wyeth’s good nature, along with everybody else’s. Layton may be the most complex character in the novel, a contradiction of bravado, posing, showmanship, charisma, generosity, and rare political gifts, capable of drawing and repelling from moment to moment.

How these friendships play out within the larger tale of fortune-seeking, diplomacy, fear, prejudice, and wonder makes a stirring story. And as Wyeth remarks about the vanishing game, you sense that he represents a dying breed himself, and that he knows it.

Into the Savage Country does end a little neatly, but I think few readers will object.

Disclaimer: I obtained my reading copy of this book from the public library.