Tags

1960s, book review, Britain, Cambridge spy ring, Cold War, espionage, Helen Dummore, historical fiction, literary fiction, morality, national security, Naval Department, suspicion, thriller, twentieth century

Review: Exposure, by Helen Dunmore

Atlantic, 2016. 391 pp. $25

Simon Callington is a decent man, the dutiful Englishman. He’s a devoted husband and father of three, bright but not brilliant, content with modest pleasures, too self-effacing to say no when maybe he should, too slow to realize that others don’t play fair. In other words, Simon is a perfect fall guy. And since this is 1960, when Soviet spies are turning up inside the British government–in fact, his immediate superiors in the Naval Department have been “batting for the other side” for years–a fall guy can be useful.

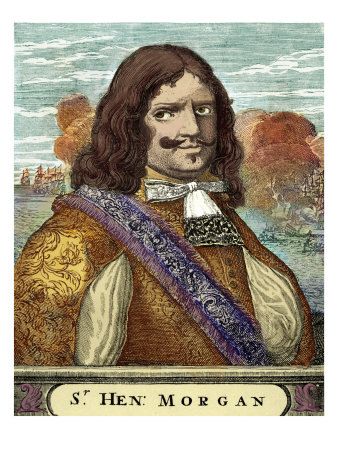

Harold Adrian Russell “Kim” Philby worked for British Intelligence but was actually a Soviet agent. One of the so-called Cambridge Five, men who attended that institution and spied for the USSR, Philby defected in 1963. This image comes from a 1990 Soviet postage stamp (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons).

The story all starts innocently enough. Giles Holloway, an old friend, mentor, and immediate superior, calls Simon at an inconvenient hour to have him rescue a file from a place it should never have gone. Simon agrees, only because he can’t say no to Giles, part of which goes back to their days at Cambridge, when they were lovers. But Simon will have ample time to wish he had said no, because one look at the file tells him that neither man should have seen it, and Giles’s briefcase, which Simon comes across, contains more of the same. Rather than return the file to the office, as Giles wants, Simon brings it home. From there, his life unravels.

With Exposure, Dunmore proves again why she’s among my favorite writers. She’s written a thriller as gripping as any, using Simon’s very ordinariness and decency to devastating effect. There’s no cloak-and-dagger here, no secret that will explode the universe if it falls into the wrong hands, no mole who must be uncovered before he or she compromises national security. Rather, it’s how those who act to protect national security are destroying the decency and moral compass that Simon represents, and they do so without a second thought, certain of their righteousness. So yes, the world is at stake after all, for what happens when decency and moral compass mean nothing?

Consequently, Exposure has to do with how the government Simon serves repays his loyalty, and how they hurt him, his wife, and children. Once suspicion falls on him, he has no friends, and the people he might have counted on for support, like Giles, will gladly sacrifice him to their own interests. Simon’s only ally is his wife, Lily, a woman of great resourcefulness. However, Simon refuses to tell her anything that might compromise her, and Lily, who can be difficult to reach, has a secret of her own that she won’t share.

Dunmore excels here, deriving so much tension from unwillingness or inability to communicate that at times you want to howl. But there are good reasons for it, which, typical of her fiction, come from within the characters. Lily, a German Jew by birth, grew up living “in fear before she knew why she was afraid . . . knowing that people hated her,” and though she escaped her native country, she can’t escape herself. Once Simon is arrested, Lily rebuffs her friends, believing that she mustn’t taint them, and concentrates on protecting her children as best she can.

Another thing I like is how Dunmore contrasts the offhand, charismatic Giles with his mousy, submissive underling. Early on, Giles observes:

We aren’t meant to see ourselves as others see us. In fact it would be a bloody dull world if we did, because no one would ever make a fool of himself again. We might as well accept that we’re put on this earth to make unwitting entertainment for other fellow men, and get on with doing so.

All that sounds very nice, blasé wisdom for the Cambridge common room. But without ever saying so, Dunmore shows what happens when Simon, dull as he may be in comparison with Giles, actually tries to connect with life instead of looking at it as a game. His plight may furnish entertainment for the men who want to sink him, but everyone else is in great pain.

The only false note in this portrayal concerns Simon’s sexuality. If he was homosexual at Cambridge and found it exciting, why has he given it up? He may think of it as a youthful road he no longer prefers to travel, and his marriage is plainly substantial. Yet Giles still exerts a pull over him. Also, Giles’s boss, Julian, though a master of the nasty innuendo and capable of intimidating just about anybody, seems two-dimensional. Almost every time he appears, the adjective cold sticks to him like Arctic ice on bare skin, but that doesn’t satisfy me.

The first book I reviewed for this blog was The Lie, a lyrical, heart-rending tale of rootlessness that’s still my favorite of all those I’ve written about here. Though Exposure deals with a different subject, it’s a worthy companion, and I highly recommend it.

Disclaimer: I obtained my reading copy of this book from the public library.